A Most Memorable Year By John M. Packard, M.D.Hello

I looked up suddenly at the shrill train whistle and saw my train pulling slowly out of the station. I had just stepped off to get a paper and was listening for the conductor’s “All aboard!” that signaled a train’s departure in the U.S. But this was 1937 in Rugby, England, and I was sixteen, alone, and scared as I saw the train with all my belongings heading out towards Liverpool without me. Dodging the crowd, I ran after it and pulled myself aboard, thanking my lucky stars that English trains had running boards and doors to each compartment. It was the start of a year that changed my life forever.

During my senior year at Taft, 1936-37, and after I had been accepted into Yale, Dad mentioned several times that he thought I was too young (16) to enter college and had decided to send me to Andover for a year. I saw no benefit at all in attending another American prep school for a fifth year, and so, without telling Dad, I applied for an International Schoolboy Fellowship, and was selected for St. Columba’s College, Dublin!

There were about 40 of us exchange students from prep schools in the U.S. who sailed from New York to Le Havre, France, in early September 1937 on the Queen Mary, chaperoned by representatives of our sponsor, the English-Speaking Union. We spent a couple of days sightseeing in Paris, where I had spent a month during the summer of 1935. Then half the students departed for their German schools (what an experience they had!). The rest of us left for Winchester School in the south of England for three days of orientation and sightseeing in London, Windsor, and the south of England. Finally eighteen of the boys were on their way to schools in England, one went to Campbell College in Belfast, Northern Ireland, and I was on my way to Dublin in what was then the Irish Free State.

The ferry from Liverpool docked in Kingston, Dublin’s port. I had met three or four other SCC students on the ferry, so we hired a cab to take us to the College, which was much smaller than I had expected. The Warden, the Reverend C. W. Sowby, and his wife greeted us, as did my housemaster, Mr. George White, the Bursar, and Head Prefect Rutherford. Then I was on my own in a 16 bed unheated dormitory.

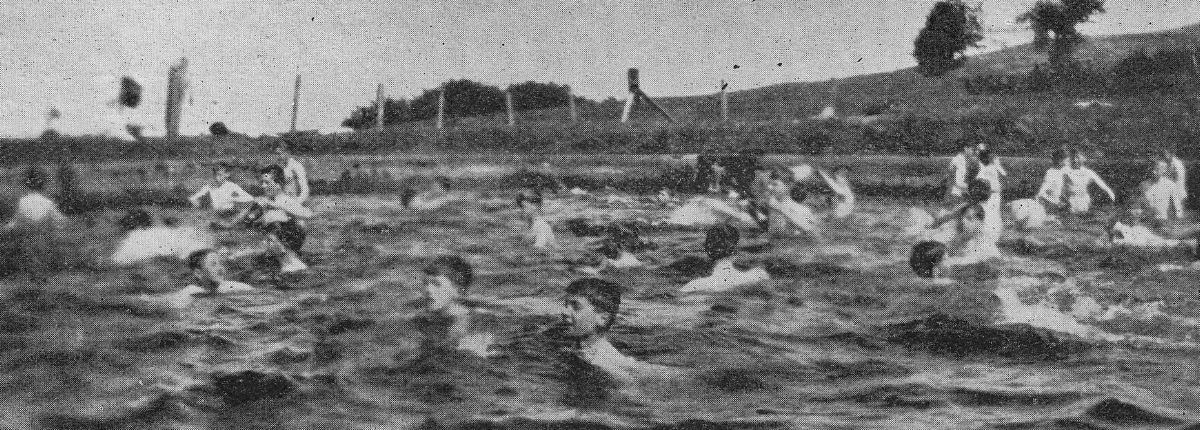

St. Columba’s College is a Church of Ireland (Anglican) private boarding school, founded in 1843. It is nestled on the side of a low mountain six miles south of Dublin. From the deer park above the College one can see Dublin and its harbor, the Irish Sea to the east, the ruins of the Hell Fire Club on Mt. Kilmashogue to the west, and on a clear day one can almost see Belfast to the north. When I was there, the buildings were old. None were heated, but the faculty apartments and some of the classrooms had fireplaces. I never saw a fire lighted in any classroom, however. Part of the roof of the changing room (there was no gymnasium) had blown off some years before, but this was during the great depression and there were no funds for repairs. There was a small unheated swimming pool up in the deer park. The toilets did flush, but many were outdoors, with a roof and walls and swinging half-doors for each stall. Some of the senior students had “fags”, younger students who polished their shoes and ran various errands for them, as in the English public schools epitomized in Tom Brown’s School Days. One of their assignments at St. Columba’s was to go out and warm up the toilet seat on cold days!

The faculty all wore mortarboards and ankle-length black academic gowns over their gray slacks, jackets, and ties. We students also dressed in coat, tie, and black “scholar’s gowns”, which came just below the hips. On Wednesdays and Sundays the faculty wore their academic hoods and we wore stiff white collars, black ties, and on special occasions, white surplices to chapel. We all had little skullcaps embroidered SCC, which we had to wear whenever we left the College grounds. On Sunday afternoons the College grounds were often declared “out of bounds”, so we either walked in the neighborhood for four hours and had a cup of tea in a nearby teashop or, if lucky, had family or friends pick us up for a drive in the country.

It was a surprise to find that we were at the same latitude, 54 degrees, as Hudson’s Bay, so in the winter the sun rose at 8:00 am and set at 4:00 pm, while in June it rose at 4:40 am and set at 9:20 pm. The winters never got very cold because of the Gulf Stream hitting the West coast 120 miles away, but temperatures in the upper 30’s or lower 40’s made scarves and multiple sweaters necessary. Because it was difficult to write or turn pages while wearing gloves, many of the students, including myself, developed chilblains on the back of the hands: large painful blisters, which rarely ruptured.

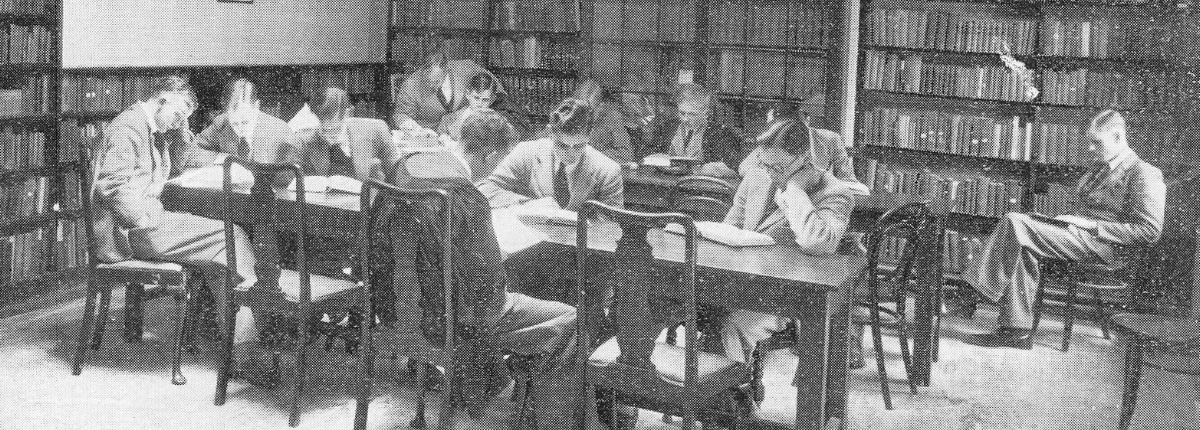

Weekday mornings started at 6:00 am with all of us ordered upstairs for a cold shower. Then breakfast in the refectory at one of the three long tables. The faculty ate at the “high table” on a dais at the end of the room. A blessing in Latin, which was chanted on Sundays, always preceded meals. Then came required chapel, classes, and lunch. Classes were held on Saturday mornings, too, with sports every afternoon. Holy communion was offered early Sunday and Wednesday mornings before breakfast, with chapel following breakfast. The Church of Ireland leaned over backwards to avoid any Papist tendencies, so there was no cross nor candle` on the altar. The prayer book was vintage 1770 and while the words of many of the hymns were familiar, the tunes were different, which was somewhat disorienting. There was usually another chapel service before dinner on weekdays. Roll call came at supper, which was really high tea. We studied in the library or classrooms. I missed Taft’s double rooms with desks for study.

The meals, while nourishing, didn’t have much variety. Breakfast consisted of eggs and bacon or sausage, scones, and tea. The noon meal was the big one, with mutton, rabbit, liver, fish, or, occasionally, beef; rutabagas, turnips, parsnips, and occasional squash; and always boiled potatoes. Dessert was some sort of pudding or pie, with tea or water to drink. The evening meal was much like breakfast, with tea, eggs and bacon or kippered herring, and a variety of breads. We never had a salad or fresh fruit served to us, but we could buy fruits and various sweets in the “tuck shop”. Soon after I arrived I requested and was granted a glass of milk at each meal, which most of the boys thought was rather odd. The entry in my diary on Jan. 18th reads,” Find I don’t mind the cod liver oil so much any more”, so evidently all of us got a daily dose.

Weekday afternoons were for sports. Rugby football in the fall, field hockey in the winter, and cricket in the spring. Oddly, soccer was not one of the sports. There were tennis and handball courts and the pool, all outdoors. We were each assigned a locker in the roofless and unheated changing room, but I don’t believe we washed our sports clothes until the end of each semester. (Thank goodness half the roof was gone, or we couldn’t have stood the stench.) Senior boys had the option of washing up after sports in one of two long tubs, two boys to a tub. The water was hot at first but soon cooled off and became muddy, since the tubs were filled just once a day. After one experience in cold dirty water I elected to join the younger boys in the cold showers! After supper we studied and could take a hot shower upstairs, although the water pressure was so low that the water was cold by the time it reached our knees. Mr. White turned off all the hot water when we were done.

There were about 120 boarding students in the six “forms” (grades). I was assigned to the sixth form and was in the enviable position of having been accepted at Yale for the next academic year, so there was no pressure to get good grades. I found that my preparation at Taft had me slightly ahead of my peers in English lit, about the same in science, and somewhat behind in math. I enjoyed the classes and the fine library. Mr. Sowby (we called him “Soss”), Mr. White, and the Chaplain all loaned me books, too. Students were called by their last names; if there were two boys with the same last name, the elder was Smith major and the younger Smith minor. A third Smith would be minimus, and then it went quartus, quintus, etc.

One of the differences between Taft and St. Columba’s was the form of punishment. I remember being fined six pence (12 cents) for spilling milk at the table. More often, the birch rod across the buttocks, wielded by a master or prefect, was the usual punishment: one lash for being slow getting into bed at lights out, three for fighting, and up to seven for serious infractions. But once the sentence was carried out, the slate was clean. No accumulation of demerits, as at Taft. I managed to avoid the rod.

Although I was somewhat disappointed when I first heard that I was not assigned to an English public school like Rugby or Eton, I found myself most fortunate. The Irish schoolboys were much friendlier to me than the English were to the American exchange students I spoke with later. During the fall, Mr. Sowby invited Mr. Cudahy, the U.S. Ambassador, and his wife for luncheon to meet me, and later introduced me to Mr. Balch, the U.S. Consul General, and his family. Mr. Balch in turn arranged an interview for me with Eamon deValera, then the Prime Minister, and invited me several times to the American Legation in Phoenix Park. The Cudahys invited me to their Thanksgiving reception, which was particular fun – lots of good food, nice people, and dancing, even with Maureen O’Sullivan, a young actress. The Balch’s son Henry was a medical student at Trinity College, Dublin, and their daughter Sylvia was a year or two younger than I. They invited me to their home on Merrion Square a number of times; I especially remember the keg of beer in the basement!

Parents of my classmates often invited me out for Sunday dinner, as did Dr. Denham, the father of Peter, who had been an exchange student from SCC to Taft several years before. We would drive around the lovely countryside, down to the shore, or as far as Glendalough on these Sunday afternoon drives. The city had many museums, old churches, and other points of interest. Visits to the movies or the Abbey Theatre were frequent, but required an “exeat” (permission slip”) from old Soss himself. And we explored the roads and lanes around the College on foot during our free time. “Keepers” was a favorite farmhouse nearby that served high tea with eggs and bacon, scones, Devonshire cream and strawberry jam in front of a peat fire, with its wonderful aroma. Lam Doyles was an old pub, where we occasionally sneaked in for a Guiness’ stout and smoke (seven lashes if caught). There was always something to see, do, or learn – even the Gaelic on the road signs.

In mid-November Mr. Sowby invited me and another classmate to spend a few days in Belfast, where we visited Fuller, the exchange student at Campbell College. His College was a lot bigger than SCC, and his experiences similar to mine, except that Ulster had no American Legation. If there were a Consul General, Fuller had not met him.

Exchange students in those days were assigned to schools, not to families with children who attend the same school, as is usually the case today. This meant that we had to make friends with our classmates and persuade some of them to invite us to their homes for the holidays. I was certainly fortunate in my choice of friends. The first two weeks of Christmas vacation were spent at Roscrea, County Tipperary, 75 miles southwest of Dublin, with Bill Bridge and his mother and sister Doreen (his father had died). They were most hospitable. Bill and I did some duck hunting, explored the countryside, and watched hunters on their horses in their red coats ride to the hounds. Bill volunteered for the RAF during WWII and was part of a “servicing commando” unit, which landed in Normandy on June 7, 1944, and prepared an emergency airstrip, which was the first landing strip open to the Allies since 1940. Later he became a law clerk, and finally ended up as a psychiatrist in Vancouver. He and I have corresponded regularly for 65 years, and I visited him and his family while attending a medical meeting in Vancouver.

The last half of the month-long holiday I spent with Mervyn Meredith and his mother and stepfather in Loughrea, County Galway, in the west of Ireland, not far from the beautiful Connemara peninsula, which they showed me with great pride. Mervyn’s father had been a pilot who died in a plane crash in Australia. His stepfather was a priest in the Church of Ireland. It was Mervyn’s mother, Aileen Cooke, who persuaded me during that Christmas holiday to switch my career goal from engineering to medicine. It did indeed change my life, for which I shall be forever grateful. “Granny” Cooke published a book on ESP when she was 73! She and I corresponded regularly until her death on New Year’s Day, 1990, a few days short of her 100th birthday. Ann and I named our first-born son Michael David after the Meredith’s son. I visited Mervyn in 1940 or 1941, when he was stationed in Kingston, Ontario, training to be an aviator in the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. Later he was decorated for leading the squadron that sank the German warship Tirpitz in a Norwegian fjord. During the 1980’s and 1990’s Ann and I visited Mervyn and Elizabeth several times. He is now a retired solicitor in Taunton, England

Homesickness was not a problem, in part because I had already spent four years away from home at Taft, in part because there was so much to see and do, and largely because the students and faculty made every effort to make me feel welcome. All communication with the family was by letters, which took 7-10 days each way. There was no airmail and no transatlantic telephone. Cables (telegrams) cost $1.00 per word, including address and signature, and a dollar in those days could buy 10 quarts of milk or 20 cups of coffee. Thus when I wrote Dad toward the end of the school year, asking permission to spend some time in France before coming home, his response by cable read: “Packard, 95820, Dublin, No”!

Easter vacation started on March 24th with Richard Eaton and his family on their 30-foot yacht “Janet”, motoring up and down the River Shannon for a week. It was their boatman who helped me select a pipe and plug of tobacco and showed me how the fill the pipe. Thus started an enjoyable habit, which lasted until the year 2000. We spent another delightful six days at the Eaton’s home in Dublin. (There are a number of references in my diary about Dick’s sweet sister Barbara, and later a note that I was homesick for the first time – for the Eaton’s!). Then came a quick succession of short visits: two days with the Chapmans, including a day at the Calary Point-to-Point horse races and visits to museums, three days with the Hurleys, and another three days with Peter Denham. Peter put me on the ferry for Holyhead, where I caught the train for Stratford-on-Avon and a remarkable visit with 80-year-old Kate Meadows and her elderly husband.

Kate was a distant cousin who had been the cashier at the Shakespeare Theatre and had many great stories to tell. An entry in the diary reads: “M’s very considerate, but Mr. M. won’t talk and Mrs. M. won’t stop.” But they were great stories! Mr. Meadows and I bicycled all around that lovely Cotswald countryside and visited all the proper tourist attractions, including the great Warwick Castle. Kate arranged for me to unfurl the Norwegian flag during St. George’s festival, where I met the Lord Mayor and Mayoress. The Easter service in the church where Shakespeare is buried, right on the banks of the Avon, was particularly memorable. I stayed with the Meadows for thirteen days and managed to see four or five Shakespeare plays in that magnificent theatre. But the wonderful vacation finally came to an end on April 26th, and back to St. Columba’s I went, by train, ferry, and taxi.

Trinity term started out rather cool, but great for tennis and walking. Classes and chapel as usual until May 5th, when Mr. Sowby took five of us for a four-day visit to Bryanston School near Blandford in south central England. Why we went is not explained in my diary, but the school was much bigger than SCC, with a wireless room, photography lab, carpentry shop, printing press, pottery and art lab, squash courts, and offered crew as another sport. On one afternoon we explored Salisbury Cathedral and the next day visited Corfe Castle where Edward II was murdered, and enjoyed a picnic lunch atop the white cliffs of Dover. On May 9th I left the group to keep a luncheon date with Lord and Lady Astor.

Let me backtrack a moment. When my Godfather, Dr. J. Woods Price, heard that I had arranged to spend part of Easter vacation in England, he mailed me a letter of introduction to his cousin, Nancy Langhorne Astor. The three Langhorne sisters were great beauties in Virginia; the older sister married a Mr. Gibson and was made famous as the “Gibson girl”. I don’t remember what happened to the second sister, but Nancy married John Jacob Astor, publisher of the London Times, and moved to England. In time, Mr. Astor was knighted. Lady Astor became active in politics and was the first woman to be elected to Parliament. Uncle Woods thought that paying my respects to such well-known persons would add to my education and be one of the highlights of my year abroad – and indeed it was!

I mailed Uncle Woods’ letter well in advance to the Astor’s London address, explaining that I expected to be in London on May 9th and asking if I might stop by to pay my respects. A note from her secretary arrived soon after stating that the Astors would be in their country home on that date and would be delighted to have me for lunch, along with all the Rhodes Scholars in England at the time. She carefully explained the train I should take in order to reach Cliveden by lunchtime and that a car would meet me at the station.

I took the train from Blandford to London on the appointed day, but for some forgotten reason missed the train to Cliveden. In those days one never made long-distance phone calls but telegraphed instead. So I telegraphed my apologies and gave the new arrival time. A chauffeur dressed in a purple uniform with black stripes down the pant legs met me at the station and showed me to a purple and black-striped Bentley. On the way he explained that Cliveden was one of the larger country homes in England, with 40 gardeners and about the same number of servants in the house. It had been converted to an Army hospital in WWI, with Sir William Osler as chief of medicine. More recently Ann and I have seen it on the British version of “Antique Roadshow”. Eventually we turned in through the gate and proceeded up the mile-long, tree-lined, winding drive to the front door, where two Rolls Royces, two Humbers, and other cars were parked.

A forbidding looking butler in a morning coat met me at the door and took my second-hand reversible raincoat with some disdain. (I had bought the coat from a Taft classmate for $10.00.) The butler led me through a large foyer filled with statuary, as I recall, and into a large dining room, where he announced “Mr. Pack-ard” to the four people seated at the small round table in the center of the room. Before I could ask where the Rhodes Scholars were, Lady Astor explained that they had gone ahead and started lunch, and that I should sit down, eat, and catch up before talking. She then introduced me to her husband, sitting across from her, to her niece, whose name I forget, and to Lord Lothian, who was appointed Ambassador to the United States the following year. (He committed suicide the year after that.) Heady company for a seventeen year old!

Lord Astor, after greeting me, continued dictating to his secretary, seated on his right. Lady Astor resumed writing a speech for Parliament, using a table beside her containing a dictionary, a Thesaurus, and a Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations, and occasionally trying a sentence or two out loud. Lord Lothian and the niece continued their conversation about free love. I was all eyes and ears!

There was plenty of time to read the hand-written menu at my place (in French), to notice the four footmen, dressed in – you guessed it – purple and black-striped knee britches, who were serving the food, and the dozens of purple and gold side-chairs around the walls. The butler would occasionally enter and read a telegram from the Duke and Duchess of So-and-So, who regretted some invitation, or from Lord and Lady Somebody Else, who accepted. When I finally caught up with the others, Lady Astor asked about my school and what I had done during Easter vacation. When I eventually mentioned Uncle Woods, she snapped her fingers and said, “Now I know who you are – you’re Cousin Woods Price’s favorite Godson!” It was most embarrassing; my letter had been sent so far in advance of my visit that no one had remembered who I was!

But worse was yet to come. At the end of the meal Lady Astor had me stand up, raise my right hand, and swear that no drop of alcohol would ever touch my lips. I did raise my right hand, but also crossed the fingers on my left hand behind my back to negate the promise. (I broke the promise within eight hours.)

After lunch the niece showed me two of the secret passages in the great house and took me out the back and down a grassy slope to a great oak at the edge of the river Thames, when Sir Edgar Elgar is said to have written “Hail, Brittanica”. The 60 Rhodes scholars had arrived by bus by this time and were out on the back terrace. The Life photographer with the group went to find Lord Astor and found him out front chipping golf balls. The butler found my disreputable reversible, and the uniformed chauffeur drove me back to the station. What a luncheon it had been!

I caught the train back to London, collected my suitcase from the Left Luggage department and boarded the train for Liverpool, where I caught up with my classmates from St. Columba’s. We boarded the overnight ferry to Dublin, proceeded to the dining room for dinner, and thence to the bar, where, despite my pledge to Lady Astor, we had a liqueur apiece. But they were expensive, so we pooled our funds and ordered a bottle of port. When that was gone, we spent the last of our money on two bottles of beer, and when they were emptied, staggered off to our staterooms.

It was one of those stormy nights when one clutched the mattress to keep from falling out of the bunk, but also kept one foot on the deck to prevent the room from spinning around. It seemed endless. But daybreak came at last, along with a splitting headache. Mr. Sowby drove us to College; there wasn’t much conversation on the way. We arrived just in time to put on our stiff collars, black ties, and scholar’s gowns, and line up with the rest of the students to march into chapel. As we read Psalm 30 and reached Verse 5: “Weeping may endure for a night but joy cometh in the morning”, we three looked at each other and shook our heads – but very slowly.

Recovery was quick, however. Two days later the Sowbys and I were invited to another reception and dance at the American Legation, where I met Sir John Keans, Lord and Lady Meath, General Brennan, and danced with a Mrs. Guiness, Mrs. Cudahy, and a number of nice girls.

Confirmation on May 20th was one of those white surplice days, when everyone dressed up to impress His Grace, the Most Reverend Archbishop of Dublin, who arrived in gaiters, to my delight, and signed the guest book “John Dublin”. The College served a better lunch than usual that day.

At the end of May, Fuller, the American exchange student at Campbell College, and a group from Bryanston School arrived for several days. They attended classes with us and watched whatever sporting events were going on. I’m not sure what the purpose of these exchanges was, but everyone seemed to enjoy them. It was about this time that I began planning my trip home, and settled on a small Cunard ship, the Athenia, sailing from Belfast to Montreal.

In early June I was invited to the colorful 900th anniversary celebration of Christ Church Cathedral in Dublin. I still remember the three loud bangs on the great west doors, which swung open for a procession of choirs followed by the ten bishops and two archbishops of the Church of Ireland, each accompanied by a priest carrying the bishop’s crosier. Quoting from my diary, “Good singing and excellent sermon, long service. Fascinating girl sitting in front of me. Will I see her again?”

Then it was back to Belfast and Campbell College for another three-day visit in mid-June, where I met a Major Henderson and his family. He had spent 15 years in the USA and had agreed to take care of me after school was out and before the Athenia sailed. I don’t remember who put him in touch with me (or vice versa).

Toward the end of June, Mr. Sowby and I attended the impressive installation of President Douglas Hyde as the first president of Eire in St. Patrick’s Cathedral. From my diary, “Soon Dougie came in after much cheering outside. Sat about twenty ft. from us. Very old and rather unsure he looked. Saw HER again. 3rd time. Lucky?” I never did meet her, alas!

There was another big reception at the American Legation on the Fourth of July of course. An Irish band played, the Canadian jumping team performed, and I met the Papal Nuncio, DeValera again, and several foreign dignitaries.

The school year ended July 27th, and once again the Eatons took me under their wing for a long weekend sailing up and down the Shannon on the “Janet” as part of a great regatta. We had a tearful parting on August 3rd before I traveled to Belfast. The Hendersons were waiting for me at the station, and were most kind; our visit to the Giant’s Causeway was unforgettable. It truly deserves to be one of the Seven Wonders of the World. On the evening of August 5th Major Henderson helped me through Customs and on to a tender to motor out to the Athenia, which I boarded at 2:15 AM.

The Athenia was a small ship and I was in third class in a cabin with two other men near the bow of the ship. The bunks were hard, the blankets didn’t tuck in, there were no closets nor drawers, no ventilation, and no lock on the door! The laundry was right below us. It was not a fun trip, but I had plenty of time to reflect on what an unusual experience I had had, and on how many kind people had been part of it. I had certainly gained self-confidence and self-reliance as well as an appreciation of another culture. I had gained many friends, and best of all, had changed my career goal from engineering to medicine. Now I was ready to take on Yale!

We finally reached the St. Lawrence River, stopped at Quebec, and docked for good at Montreal on August 15th. Dad, Aunt Charlotte, and the girls were on the dock to meet me. To insure that they would remember the occasion, I wore the green kilts, sporran, and tam of our Irish Boy Scout troop when I walked down the gangplank. It did make an impression! As an aside, one year later the Athenia was the first passenger ship torpedoed by a German U-Boat at the start of WWII.

Readjusting to being home with Dad and my two younger sisters wasn’t easy. I couldn’t believe it on my first night back when Dad cautioned me to be sure and wear my rubbers when I went out because it was raining!

The Aftermath

It wasn’t possible to thank all the people who had made my stay at SCC so meaningful, but an opportunity arose in 1973 to be the host family for Krid Asvanon, the 16 year-old son of a Thai physician. Dr. Kovit hoped that Krid would stay in the States through college and medical school. This seemed to be an indirect way for me to pass on to others some of the benefits I had received as an exchange student. With the blessing of Ann and our seven children, we took Krid into our family and adopted him in 1979 when it appeared that it might be helpful if his family had to flee Thailand during a political coup (they didn’t have to).

Krid didn’t go to medical school, but he did graduate from high school, the University of Alabama, and the California Institute of the Arts with two BFA’s and an MFA before returning to Bangkok in 1988 as an advertising executive. He subsequently married and now has two children. Accepting Krid into our family worked so well that we hosted Rowena, an Australian 17 year-old girl during 1979-80; Eva, a Finnish girl the following year; and Hector, a Guatemalan medical student, for three months in 1987. Our youngest daughter, in turn, was an exchange student during 1981-82 to a Canadian family living in a 700-person village in Quebec, where only French was spoken. And Krid’s 17-year-old daughter Tippy was an exchange student in Arizona during 2003-2004, while his 14-year-old son is currently (2005-06) an exchange student in New Zealand!

Ann and I still get warm feelings when the students’ letters, and now e-mails, address us as “Mum and Dad”. Our whole family has benefited in many ways from living with these fine young people from such varied international cultures.

Best of all, thanks to good health and lots of frequent flyer miles, Ann and I have been able to visit three of them and their families on their home grounds. In 1995 we flew to Aukland and boarded a ship, which cruised around New Zealand and ended at Sydney, where we spent ten days with Rowena and her parents. She still lives there with her physician-husband and three children. In 1998 we visited Bangkok and stayed with Krid and Anne and their two children – even had dinner with the Queen of Thailand! In 1999 we spent a day in Helsinki with Eva and her research-scientist husband, just a week before their third child was born. And we stopped in Taunton, England, on the way home from the Baltic to visit Mervyn and Elizabeth Meredith. While there, we paid our respects at the grave of his mother, who, in a way, had started all this in 1937…

August 8, 2001

Revised June 4, 2006